I wanted to go walk around the vineyards above the Heuriger after we finished eating but it had started to rain so we took the tram back downtown from the northern suburbs.

The first bar we went to was perfectly nice. There was nothing wrong with it. It had wraparound bookshelves on which I found a collection of writing (in English) about Portland, Oregon, including an extract by some nineteenth-century founder of the city, some lawyer from Ohio, in which the author held his thoroughgoing boosterism in check long enough to aver that Portland would never become a tastemaking city.

This bar was empty when we walked in but by the time we had finished our first glasses of clean, slightly sweet Austrian beer it had filled up with young people, the sort of people who want to think of themselves as literary in some sense but are obviously professionals of some kind. Brooklyn has bars with this kind of clientele but these people seemed less selfconscious presumably because they were Viennese and not American.

T— and I spoke about political literature, the kind available in MFA programs and the kind available these days in Manhattan basements. We talked about the widespread folly of imagining that your writing is “doing something” in the world except through its own force as writing, as a heroic gesture of refusal.

Then I convinced T— to accompany me to the Café B—. This place, despite its name, was a late-night bar which came recommended with a curious blurb in the Word document passed on to us from a Viennese friend of a friend.

“The only place in Vienna where you can find anarchists sitting cheek to cheek with Burschenschafter … It is sort of a late-night Bermudadreieck but you must behave yourself or the Wirten will kick you out. … But perhaps you have to be from Vienna to understand how strange this place is?

An enticing description with a sort of dare on top. We walked through a zone of government offices and turned onto another silent street of white institutional neoclassical buildings only to have Café B— emerge incongruously into view, advertised by a little Puntigamer-sponsored sign (an Austrian beer whose catchphrase is Das bierige bier, which as far as I understand means “the beery beer”).

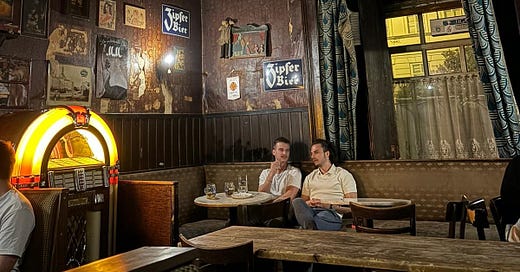

We pushed past the people smoking outside into a small, cozy little old-school-looking place with worn and scarred tables and wooden chairs, and in another room, velvet-upholstered corner booths and a jukebox which turned out to have all of maybe 20 songs on it (a typical European selection, some Euro ballads, some well-chosen tracks from Springsteen and Dylan and Cash, and some real head-scratchers, including Dylan’s “Wigwam”).

We sat in one of the dark velvet corner booths and ordered a couple of beers from the Wirten, a late-middle-aged Austrian woman with shortcropped blonde hair and crow’s feet we immediately took a liking to, and asked the Austrians at the table next to us what they were drinking. They had a small plate with two glasses of warm amber-red liquid, just a finger’s worth, and sugar cubes and coffee beans. It’s called Koks, they said. This apparently means cocaine in German slang. You chew the beans, drink the rum and eat the sugar cube.

The cafe really did have a varied clientele. There were a few middle-aged men and women in the room by the bar. In this room, with the jukebox and the velvet-upholstered corner booths, there were the Austrian good old boys who had explained Koks to us. There was a couple maybe in their late thirties in the other corner who seemed to be attempting to have sex with their clothes on. The woman, who had clambered on top of the man, was wearing a particularly garish green and orange paisley dress. Eventually the Wirten had to come over and put a stop to it. This place clearly operated like one of those “topsy-turvy households” we’d seen painted by Dutchmen in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Next to us were two girls, one stereotypically Austrian-looking (Sound of Music-type blonde etc.), while the other, darker-haired, kept glancing over at us, and they had a whole ensemble of bags including one out of which they periodically pulled a bottle of white wine—snuck into the bar because it didn’t serve wine?—to replenish their glasses. They ordered a round of Koks and instead of crunching the sugarcubes dunked them into the rum with a finger, holding them against the wall of the glass near the bottom and moving it up and down until it dissolved.

They turned out to be Brazilian, or in the case of the blonde girl, half-Brazilian, daughter of an Austrian expat from Linz who had grown up (this part was no surprise) in Rio Grande do Sul, the state where Gisele Bündchen is from and which much of the rest of Brazil considers to be really a part of Germany if not of Uruguay. Her friend was from the interior of São Paulo but was studying at the university here in Vienna and spoke excellent German. They were curious how we ended up at this bar, which was a confirmed local’s place and not on the radar of tourists nor seemingly the kind of place that tourists would like. It’s been around since the 1850s, they said. And the interior hasn’t been updated since at least the 1970s, or probably longer, which is why we like it. Except those couches over there, the blonde girl said, which they finally replaced a few years ago. The couches they had before were absolutely horrifying, disgusting, you could find all sorts of things in there … you could reach your hand in and find something from the 1940s probably … they were horrifying couches … I miss them very much …

They were impressed, and suspiciously concerned, that it turned out I could speak Portuguese: apparently they had been gossiping in Portuguese to each other, and didn’t seem convinced by my repeated (and quite genuine) insistences that I hadn’t been able to hear a word over the strains of “Ring of Fire” emanating from the jukebox (or rather over the Austrians singing along). I hadn’t even realized they were speaking Portuguese at all.

They insisted I come out for a smoke and show them exactly how good my Portuguese was and then upon hearing I lived in New York City promptly got distracted discussing some destination wedding in Hoboken (is Hoboken a “destination”?) that they were planning to attend in a few months, promptly forgetting all about me and T—, who had graciously accompanied me outside despite not being able to understand a word of Portuguese. As the girls went on and on in tedious Brazilian-bourgeois fashion about how they would certainly refuse to fly coach … it would be first class for them to New York, or business class at the very least … in search of a secret language of our own, I began paraphrasing in an ironic tone (or the closest approximation to one I could achieve in my absolutely atrocious French) what the girls were saying to each other for the benefit of T—, who spoke very good French.

Eventually we got bored and went back inside and talked to the good old boys. They also wanted to know how we ended up at this place, and why we were in “Wienna” at all. For some reason they pronounced the city’s name with a W, I think overcorrecting based on the endonym and the fact that the letter W makes a W sound in English. One had blond shoulderlength hair and was studying art history here in “Wienna” although he didn’t look the way you might expect a Viennese art history student to look. He looked like he played on a high school lacrosse team in the Milwaukee suburbs. The other had shortcropped brown hair and was studying law in Salzburg. They both were from Upper Austria and in speaking had that sort of slow-motion lilt I associate with rural Austria. They spoke very slowly and paused inexplicably between words.

“This is the last … Beisl … in Wienna,” the blond one said about a dozen separate times. “This is the only place where you can find every sort of person … young, old … left, right … up, down” (here he would grin) “even from, how do you say it? the Parliament, which for us is right here,” he said, explaining that last week he’d seen a People’s Party deputy drinking beer with his aides at that table over there.

It was very easy to bait the two Upper Austrians into inveighing against the Germans. The Germans, they said, were after all just so annoying, getting worked up into a huff whenever someone didn’t do things exactly the way they wanted, but the worst part was how they acted like they were doing you a favor by telling you off … truly intolerable … no sense of humor … by contrast the Viennese had an excellent sense of humor, though not everyone knew how to appreciate it … for example, when a Viennese man who is not especially attractive, let us say a 6 out of 10, is on a date with a very attractive Viennese woman, who is as we say a perfect 10 out of 10, then the first thing he will say to her is, I’m sure you have nothing better to do with your evening than to be here with me.

That’s the way it is in Wienna, the blond one went on, and sometimes people think the waiters are rude, but they really will warm up to you later.

And Austria? Well, it wasn’t like some other countries in Europe … the French, they like to protest, and the Dutch, maybe you saw that episode where the farmers dumped shit in front of the parliament there. It’s impressive, I see why they do it, but in Austria it’s not like that … when something happens we say, okay, we can live with it, it’s not so bad … the Labor Party arrives in government and we say, it’s okay, perhaps we can even take, how do you say, an advantage from this somehow? … the Nazis come—and here he tilted his head to show this was a joke, or mostly a joke, or at least not wholly serious—the Nazis come and we say, okay, perhaps we will benefit from this somehow …

Now, he hastened to add, or rather didn’t hasten, because Austrians don’t hasten to do anything, but he added nonetheless in a more serious voice, lest we get the wrong idea, that he wasn’t endorsing this, not necessarily, but that the fact of the matter was that it was the way the country was and he didn’t see it as very likely to change …

Well, it was getting late, wasn’t it? And the Café B— was closing, believe it or not. The jukebox was turned off, midway through “All Along the Watchtower.” We paid for our last round and the Wirten, Elisabeth, opened her black leather acccordionstyle waiter’s wallet and said fünfundzwanzig-bitte-sehr in her lurching staccato, somehow reminiscent of a Victorian innkeeper’s wife, and then it was time to go. We said goodbye to the good old boys and the Austrian-Brazilian girls. We called a car and waited for it on the deserted government-district street as the sky began to turn dark blue. And back at the apartment we slept until the afternoon.