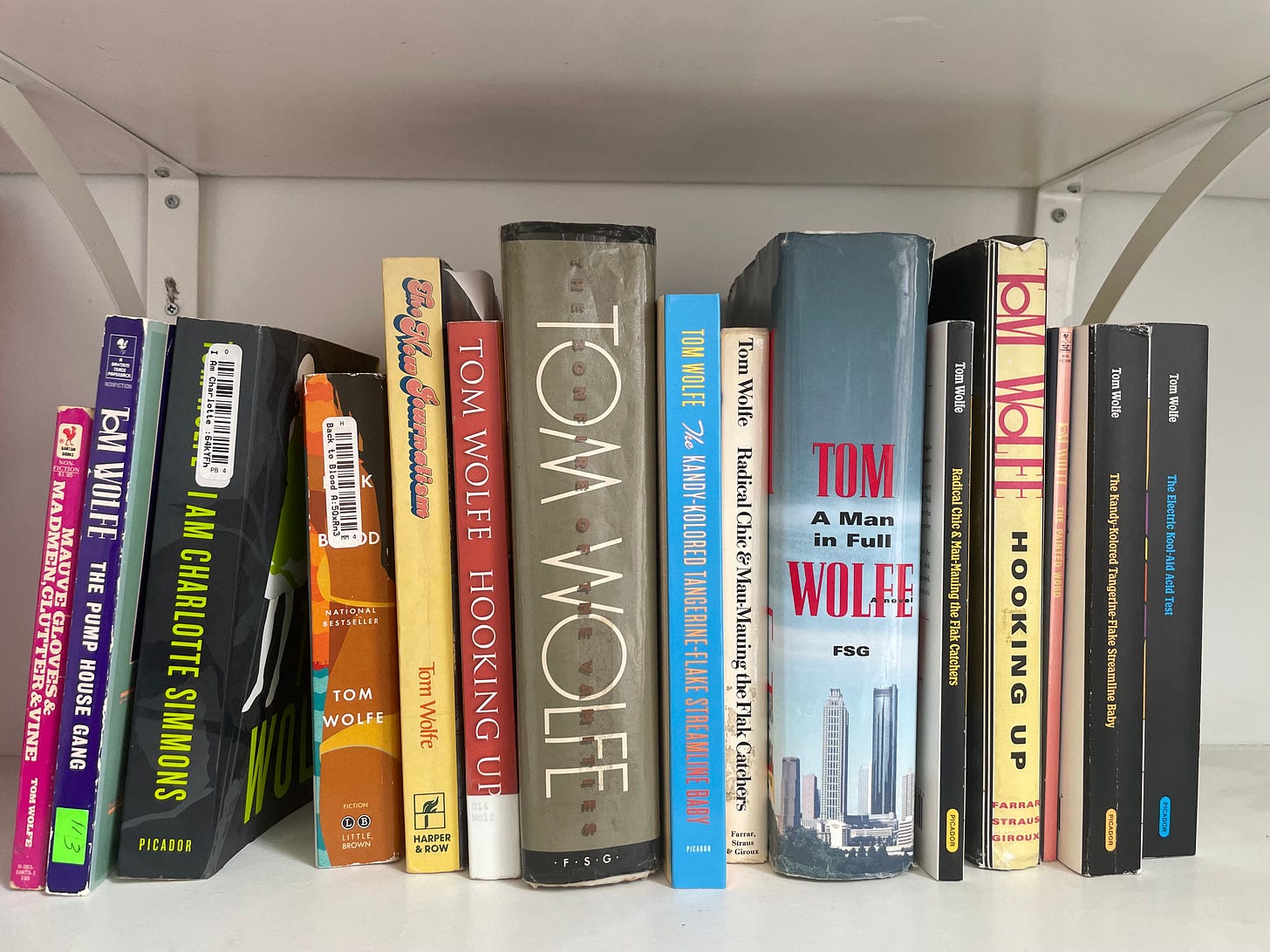

Tom Wolfe at the Strand

Stalking the white-suited dandy

Last Thursday I moderated a discussion on Tom Wolfe with Taffy Brodesser-Akner, Emily Witt and Alex Belth at the Strand bookstore, on the occasion of the release of the first set of Picador’s program of new editions of his work. I thought the occasion called for a brisk survey of his career, the sort I didn’t really have space to include in my article from last year on why no one writes like Tom Wolfe anymore. Here are my remarks—I didn’t read all of this at the event, I skipped some paragraphs, but this is what I had prepared.

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe, Jr., was born in 1930 in Richmond, Virginia, raised in an upper-middle-class family that encouraged his intellectual inclinations. After college at Washington and Lee, he completed a PhD in American Studies at Yale, where like many Southerners before him at Ivy League universities in New England, he felt somewhat at odds with the institutional culture—politically and aesthetically.

After graduating he immersed himself in the more bracing waters of newspaper journalism—which at that time still had a kind of air of cigar smoke about it—in Springfield, Massachusetts and then at the Washington Post, before finding his way to New York City, and work at the Herald Tribune—the “Trib”—which at that time, besides being the “other paper” in town, opposite the respectable New York Times, had a reputation for letting its writers go out on a limb.

But Wolfe first made his name in the New York literary scene with a 1963 essay in Esquire magazine on teenage car culture in California, “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby,” in which he unleashed an over-the-top prose style that borrowed as much from the hysterical incantations of early 1960s AM radio as it did from French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline. A dandyish figure, clad in his trademark white silk tweed suit, Wolfe became known as much for his shafts of insight into popular culture as for his brutal satires of New York City’s upper crust. He also became notorious for picking fights with symbols of New York cultural respectability, from the New Yorker magazine to Leonard Bernstein and the art world (all of it).

The three books that are out now in handsome new editions, forming the first salvo in Picador’s ambitious project of reissues from Wolfe’s extensive bibliography, are from this first phase of his career. In The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, a 1965 collection of early journalistic writing on popular culture and the New York scene, Wolfe insists that “customized cars are art objects,” that Phil Spector is “the genius” of a “baroque period” in human culture, like Cellini, and that Las Vegas is the true culmination of modern architecture—a decade before Learning From Las Vegas.

In 1968’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, about novelist turned psychedelic hero Ken Kesey and the birth of the counterculture out of the remnants of Beat Generation bohemianism, you might imagine that given often his somewhat conservative inclinations, Wolfe would single out Kesey’s acid-tripping gang for brutal mockery, bringing his combination of Southern cynicism and New York seen-it-all-ness to their naïve West Coast optimism—and he does, a little bit—but mostly, he takes Kesey’s project of creating a new way of life out of the “Formica blandness” of the 1960s with a shocking level of seriousness. It’s reading this book that we realize how serious Wolfe was in his devotion to the vital emanations of American culture. This edition features an acute new introduction by Geoff Dyer.

In 1970’s Radical Chic and Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers, two longer pieces on race relations and the status games of the American upper class, we do get the more biting side of Wolfe. In “Radical Chic,” a devastating party report from Leonard and Felicia Bernstein’s 1970 fundraiser for the Black Panther Party at their Park Avenue apartment. Drawing from the absurd mise-en-scène of Black Marxist revolutionaries at a gathering of high-society New Yorkers, Wolfe elaborates his theory of “radical chic,” or as he mostly calls it in the piece, nostalgie de la boue, in which, he argues, the upper class romanticizes the subaltern as a means of demonstrating their superiority to the middle classes. The essay dismayed the Bernsteins, who never forgave Wolfe, and earned a long and testy reply in the New York Review of Books by Jason Epstein. From that day to this, opinion has remained divided, between those who see the piece as a triumph of observation and sociological insight, and those who, like Christopher Bonanos of New York magazine, think it was “too mean.”

In 1973, Wolfe published The New Journalism, pressing his case for the literary merits of the new style of nonfiction journalism with a collection including contributions from—himself, Gay Talese, Hunter S. Thompson and Joan Didion, and cementing the term that still describes that influential journalistic style, despite protestations, including from Thompson, that it was all just a marketing exercise. If you look closely at Wolfe’s own understanding of what the New Journalism was, you notice that he conceives of it as a kind of literary class revolt. As he writes in 1973’s The New Journalism:

The literary upper class were the novelists … they were regarded as the only “creative” writers, the only literary artists. … The middle class were the “men of letters,” the literary essayists, the more authoritative critics; the occasional biographer, historian or cosmically inclined scientist also, but mainly the men of letters. They were not in the same class as the novelists, as they well knew, but they were the reigning practitioners of nonfiction. … The lower class were the journalists, and they were so low down in the structure that they were barely noticed at all. They were regarded chiefly as day laborers who dug up slags of raw information for writers of higher “sensibility” to make better use of.

The hardscrabble, semiproletarian, shoe-leather reporters, Wolfe imagined, were going to oust the effete, decadent Eastern establishment novelists from their perch at the top of the literary world’s pecking order. And creative nonfiction did indeed gain much in prestige, even if novelists still possess a certain elevated status. (In fact, you could argue from our vantage point, the more successful injection of prestige into a form once perceived as workaday was what happened to television.)

In 1979’s The Right Stuff, about test pilot Chuck Yeager and the Mercury Seven astronauts, Wolfe returned to a recurring theme of Ur-American good old boys thrust into the unwelcoming modernity of the American twentieth century—in this case, portraying the rise of the space program as the death of a kind of democratic high-modernist chivalry in the sky.

Then, after having spent years targeting the novel as an exhausted form that had to be supplanted with the likes of his new, vigorous, inventive nonfiction, Wolfe turned to—you guessed it—the novel, presenting his attempt to refashion himself as a sort of American Balzac in 1987’s Bonfire of the Vanities, a socially ambitious but formally conservative novel about the simmering racial tensions and status anxieties of New York City at its nadir. Bonfire, which first came out in serialized form in Rolling Stone (also very nineteenth-century) quickly became a cultural touchstone for its omniscient portrait of a city on edge, from commanding heights to poor periphery—and, a bit later, it also became a critically panned movie starring Tom Hanks.

More novels followed toward the close of his literary career, with diminishing results, though Wolfe’s sense of the cultural-moral-political-economic cutting edge remained undiminished: A Man in Full, about the new South, I Am Charlotte Simmons, about campus sexual assault, and Back to Blood, about Miami. Wolfe died in 2018, after publishing his last book, The Kingdom of Speech, a critique of Darwin and Chomsky that emphasizes the centrality of the human capacity for language.

Today, the biggest fans of Wolfe’s social criticism in particular are often conservatives, or else liberals who have separated themselves from the progressive cutting edge. Bonfire continues to be read widely. As stylist, as observer, as nonfiction pioneer, he continues to be worshipped across the political spectrum—although the younger crowd in New York City does so increasingly sub rosa.

In Kandy-Kolored, there’s an essay about how rich men have a secret—tailored jackets with real buttons on the sleeves, a delicious sartorial pleasure to be enjoyed in secret, since bandying about your functional buttons was considered a bit untoward. It might amuse Wolfe, were he around today, to imagine that—at least for a certain set—he himself had become a kind of literary version of this.