Chaos has been lately unleashed upon the two-million-strong American federal workforce by … the new management. Don’t let them tell you that Twitter isn’t real life when what happened to its workforce is now attempting to be wrought upon the employees of Uncle Sam!

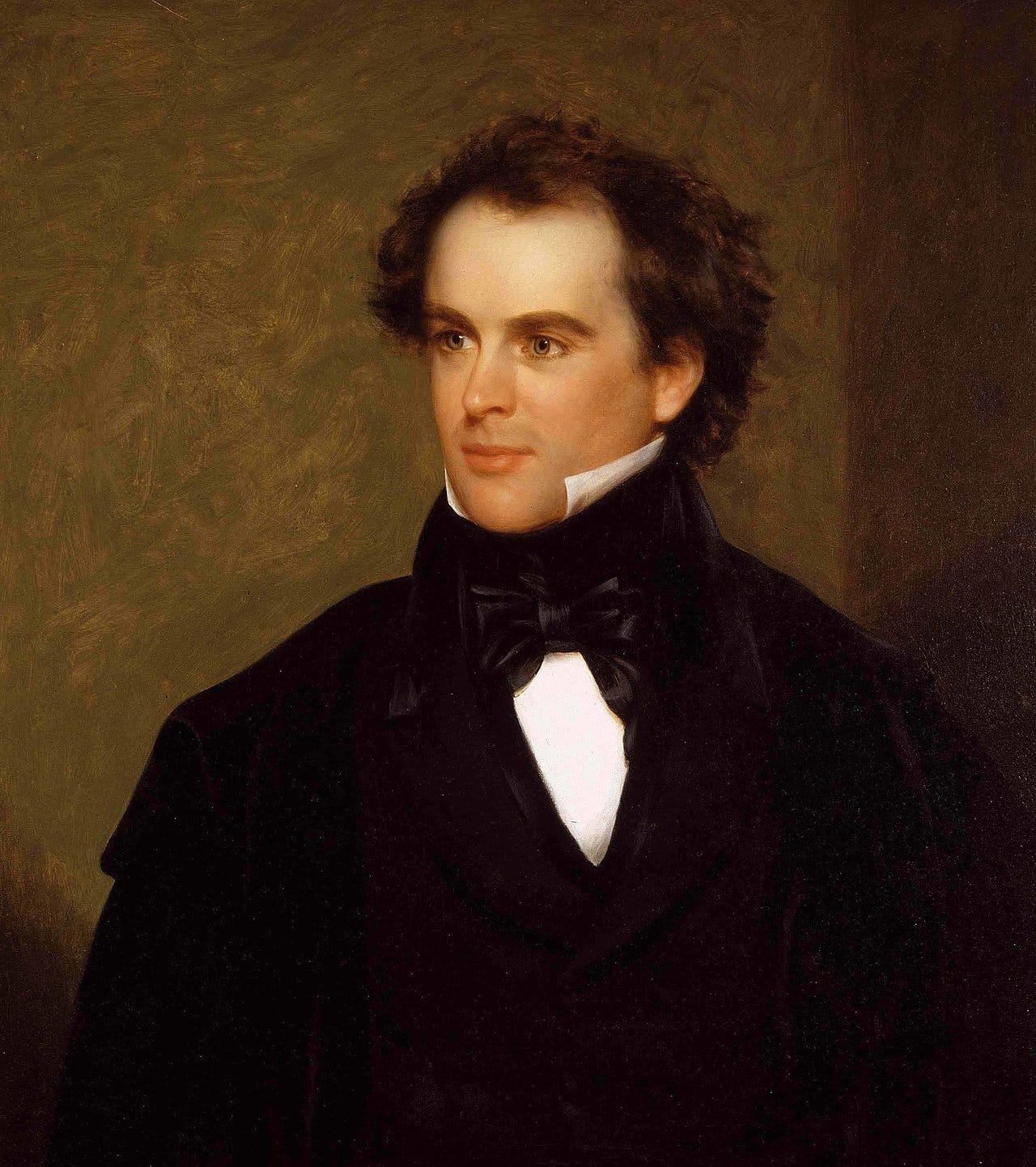

This turbulence is as good a reason as any to recall the most famous work of American literature about losing your government job: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s famous prologue to The Scarlet Letter, about his time in the Salem custom house.

Hawthorne, often short of money, served the U.S. government twice as a customs official. His first job, in Boston, was cut short by a Whig victory in the 1840 election—which prompted Hawthorne, a Democrat, to live at the Brook Farm transcendentalist commune and spend time toiling with the “dreamy brethren” there, supposedly in order to save enough money to marry. In 1846 he again obtained a job, now at the Salem custom house, but lost it again after another Whig victory 1848—this time occasioning a controversy after local Whigs attacked him for alleged malfeasance in office.

I should admit at this point that the contemptibly clickbaity headline of this squib is entirely misleading: Hawthorne was far closer to being a MAGA patriot purged by the woke Whig mob. More on that later …

He talks about the customs house job in the prologue, a kind of Bartleby-esque early workplace portrait that doubles as the frame for the (somewhat halfheartedly) framed narrative of The Scarlet Letter. It opens with a striking panorama of New World abandonment—the sad landscape of decline that is a common phenomenon in places in the Western Hemisphere where the flames of commerce or moral activity have burned and burned out:

In my native town of Salem, at the head of what, half a century ago, in the days of old King Derby, was a bustling wharf,—but which is now burdened with decayed wooden warehouses, and exhibits few or no symptoms of commercial life; except, perhaps, a bark or brig, half-way down its melancholy length, discharging hides; or, nearer at hand, a Nova Scotia schooner, pitching out her cargo of firewood,—at the head, I say, of this dilapidated wharf, which the tide often overflows, and along which, at the base and in the rear of the row of buildings, the track of many languid years is seen in a border of unthrifty grass—here, with a view from its front windows adown this not very enlivening prospect, and thence across the harbor, stands a spacious edifice of brick.

Remarkable the kind of first sentence you could get away with in the nineteenth century. The edifice in question is the customs house where Hawthorne worked alongside

ancient sea-captains, for the most part, who, after being tost on every sea, and standing up sturdily against life’s tempestuous blasts, had finally drifted into this quiet nook; where, with little to disturb them, except the periodical terrors of a Presidential election, they one and all acquired a new lease of existence.

Hawthorne complains of the stultifying atmosphere of working amid these living relics, who were incidentally mostly Whigs and therefore political adversaries, not to mention self-serving (“officers are appointed to subserve their own profit and convenience, and seldom with a leading reference to their fitness for the duty to be performed”). He found it impossible to write with inspiration during these months, drained by the grueling 3.5-hour workday.

Yet he speaks of the experience of losing his job, with the election of Zachary Taylor, as if it was a terrible trauma, comparing it (with obvious undertones of castration) to having his head chopped off by a guillotine. He seems to have evinced much the same sentiment in his private correspondence:

From Edwin Haviland Miller’s biography of Hawthorne:

"My head has been chopt off" was the way he characterized the indignity. He attacked those who in his perception had deprived him of livelihood as well as of masculinity: Hawthorne had a way of transforming situations into confirmations of lifelong fears.

But in the prologue, Hawthorne pauses to explain that although it was Jackson’s Democrats who were most famous for practicing the spoils system, it was the dastardly Whigs who really abused it:

The Democrats take the offices, as a general rule, because they need them, and because the practice of many years has made it the law of political warfare, which, unless a different system be proclaimed, it were weakness and cowardice to murmur at. But the long habit of victory has made them generous. They know how to spare, when they see occasion; and when they strike, the axe may be sharp, indeed, but its edge is seldom poisoned with ill-will; nor is it their custom ignominiously to kick the head which they have just struck off.

In Hawthorne’s time, under the Second Party System, the Whigs counted on the support of stout upright native-born Protestants, business elites, anyone connected with finance, and especially the coastal Northeast, like where Hawthorne lived in Salem … behind enemy lines. Democrats, Jackson’s party, had their strongest support in rural areas and on the frontier—and among immigrants in the cities, Irish and German. Whigs were modernizing import-substitution-industrializationalists avant la lettre; Democrats were agrarianist small-government yahoos in favor of supercharging the settler frontier and junking the banks, which just served those rich corrupt elites anyway … the common man didn’t need them!

Obviously the social context was entirely different to our own, with the frontier preserving the Jefferson-Jackson agrarian vision of the U.S. as a still sensical one and with finance in its infancy, in part thanks to Jackson’s sabotage of Nicholas Biddle’s bank; with American empire still decades away … there was no tech-billionaire arm of Jacksonianism … manufacturing was Whig-coded rather than Democrat-coded … but the comparison in terms of cultural valence and broad tendencies of affiliation under the analogy Whigs:Democrats::Democrats:Republicans presents itself rather obviously to the observer. John Quincy Adams especially presents himself to us as analogous to a familiar sort of type in our own politics, a kind of leading figure of an earlier “coastal elite,” son of the great Revolutionary hero, righteous opponent of Jackson’s frontier brutality and increasingly over time of slavery, but very possibly motivated not so much by selfless moral considerations but rather by social disdain of the uneducated and lower-class Jacksonian base, something that did much to neuter the practical effects as well as the moral force of his opposition. The sins of the Resistance … plus ça change …

Anyway, Hawthorne’s Democrat sympathies made him a bit countercultural in his Massachusetts milieu … a little disreputable. And he was a real Jacksonian—despite being a real Massachusetts patrician, descended from a famous and famously cruel family of draconian Quaker-hating Puritan magistrates. Haviland Miller explains that Hawthorne felt much more comfortable hanging out with the MAGA hat rabble … though with some Puritanical reservations … to schmoozing with the credentialed elite:

Most of Hawthorne's Salem friends belonged to the Democratic party, which was also the party of Bridge and Pierce. He shunned the company of the Salem elite who were usually Harvard graduates, Whigs, and affluent maintainers of decorum, preferring the company of middle-class Democrats, alcoholics, party hacks, and even a boozy former clergyman, all of whom he no doubt met in Salem's disreputable taverns. Yet he was often priggishly fastidious about personal cleanliness and on one occasion was worried enough about shaking the hand of "an underwitted old man . . . lest his hand should not be clean" that he duly recorded his fear in a notebook. He was often, as we shall see, secretly attracted to the rough-and-ready of both sexes. In such company he lost the shyness and tied tongue that consigned him to the role of silent observer in genteel gatherings.

One of his heroes was the greatest Democrat of the era, Andrew Jackson, who was scarcely tolerated or even mentioned in elite circles in Salem. Jackson, however, was in the tradition of the Hathornes1: virile, energetic, and more than a little ruthless. When Jackson visited Salem in 1833 after his reelection Hawthorne walked to the outskirts of the town, in the words of his sister Elizabeth, "to meet him, not to speak to him, only to look at him; and found only a few men and boys collected, not enough, without the assistance that he rendered, to welcome the General with a good cheer." Forty years later Elizabeth was still surprised: "It is hard to fancy him doing such a thing as shouting."

Some resentment towards the affiliation with the image of that hated Tennessee rube … and slaveowner, though Whigs still had some proslavery elements too … might have helped encourage local Whigs, including some of Hawthorne’s erstwhile friends, to gather together to badmouth him to the incoming administration, helping speed along his ouster from the sleepy customs house.

At least these Whig bombardments can be said to have offered a service to the history of American literature, in removing Hawthorne from a position that while allowing him to subsist also, in his own admission, cramped his creative energies. One can only hope that Musk’s crusade will lead some pink-slipped federal employee to write the next Great American Novel.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ancestors. He changed the spelling of his own name possibly to avoid too close association with the still-remembered cruelty of his forebears.